In this article, Kunwar Khuldune Shahid traces the rise of Barelvi movement as a political force since the hanging of Mumtaz Qadri who murdered former Governor. TLP was also aided by the state and is now a force to reckon with.

On August 1, 2015, 75 Ahl-e-Sunnat leaders pledged allegiance to Khadim Hussain Rizvi as he announced the formation of Tehrik Labbaik Ya Rasool Allah at Karachi’s Nishtar Park.

The Barelvi group’s charter was straightforward: “imposition of Sharia in Pakistan, and the protection of Prophet Muhammad’s (PBUH) honour.

Over three years later, now going by the name of Tehrik-e-Labbaik Pakistan (TLP), Khadim Rizvi’s party has evolved into an entity that can dictate foreign policy, mock the Supreme Court and bring the entire country to a standstill at the drop of a fatwa.

Early days

Tehrik-e-Labbaik’s creation was intended as a pressure group to prevent the government from executing Mumtaz Qadri, who had been sentenced to death for killing former Punjab Governor Salmaan Taseer.

And so it was natural that when the police commando was hanged on February 29, 2016 the Tehrik exploded to the scene with its first protest in the capital.

As an intermittent protest continued in Islamabad during March 2016, the sit-ins were finally called off following seven-point verbal agreement with the government, which carried little significance.

TLP would go on to get the signatures of the civil military leadership on those very points the very next year, owing to an external manufacturing of circumstances that the group made the most of.

The rise

While the Tehrik Labbaik would continue to be a manifestation of the radical brand of Barelvi Islam – making full use of the weaponised blasphemy law – that has become prominent this decade, the year and a half following Mumtaz Qadri’s execution would see the group remain limited to tributes for the man they felt was “judicially martyred” and issuing of scores of fatwas.

It is the latter that gradually brought Khadim Rizvi to the forefront, with his now signature foul-mouthed fatwas targeting anyone he deemed a blasphemer.

These included the state itself, and the current Prime Minister Imran Khan, who in January 2017 was accused by Rizvi of blaspheming and declared a kafir for sharing an anecdote from Islamic history.

Mainstreamed

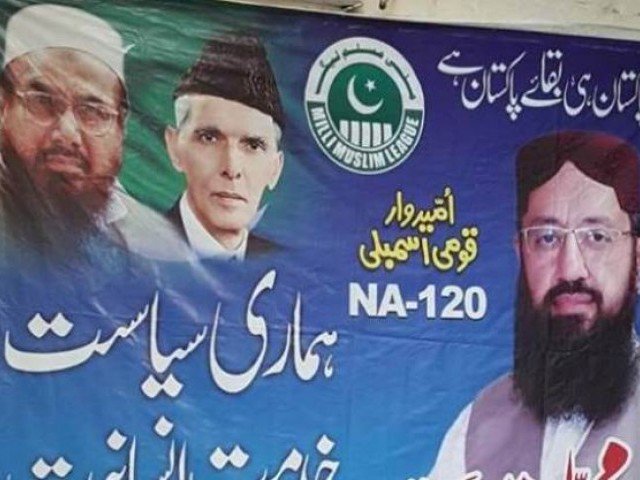

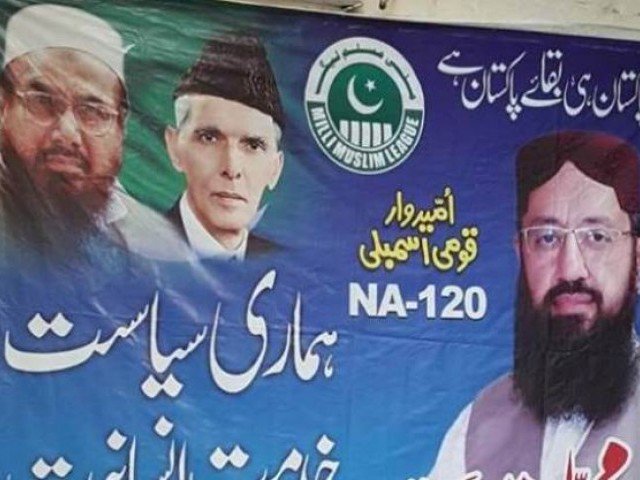

On August 14, 2017 the Milli Muslim League (MML) an offshoot of Hafiz Saeed’s Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT) and Jamaat-ud-Dawa (JuD) announced its creation in a bid to contest the 2018 general elections.

More imminent, however, was the by-election in the then NA-120 constituency of Lahore, which had been vacated by former Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif after being disqualified by the Supreme Court in the Panama Papers trial in July.

Many believe that Nawaz’s disqualification had the backing of the all-powerful military establishment owing to his trading overtures towards India, and calls for action against Kashmir bound jihadists – spearheaded by Hafiz Saeed – which formed the basis of the Dawn Leaks of October 2016 as well.

Multiple Army officials have revealed that bringing the likes of MML to mainstream was also an Army backed plan, which was not aimed at giving these groups political space, but would eventually dent the then ruling Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz’s (PML-N) vote bank as well.

Among these was the TLP as well.

The rise continues

After capturing thousands of votes in by-elections in Punjab and Khyber Pakhtunkwa, TLP found its moment in the first draft of the Electoral Reforms Bill 2017, wherein the working of the candidate nomination paper had been changed to eliminate its anti-Ahmadiyya clauses.

While the government reinstated those clauses, by then the TLP had established its parallel court demanding the head of those responsible for the changes in the original bill. In November 2017, a two-week choking of the capital through a sit-in at Faizabad Interchange ensued.

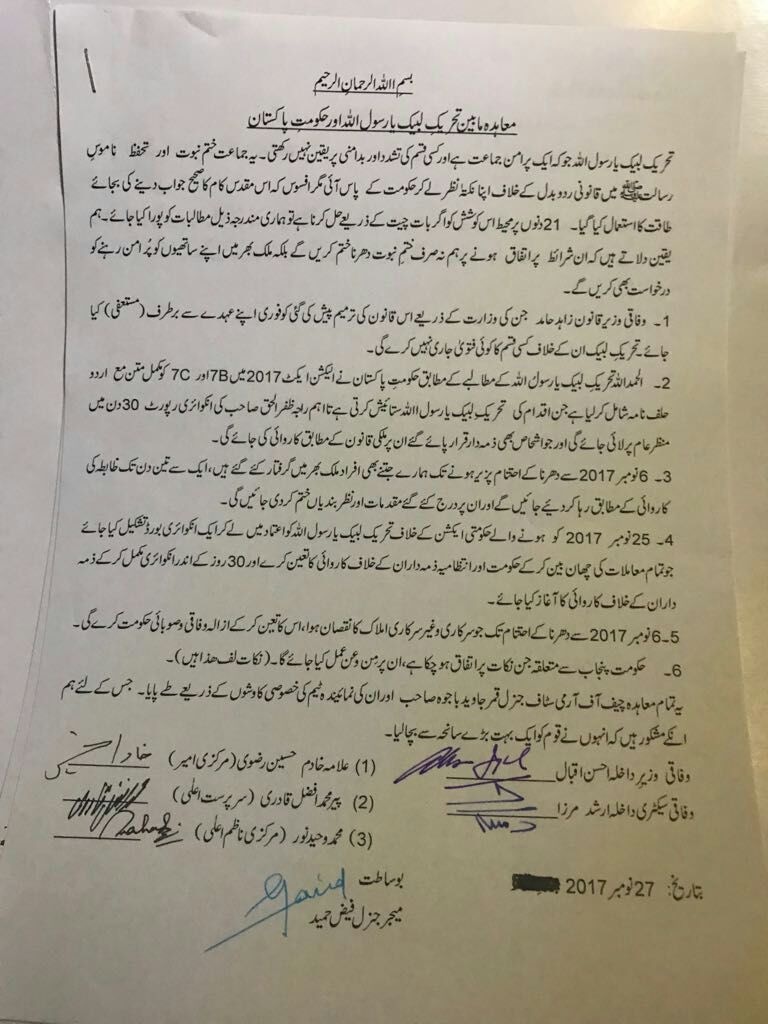

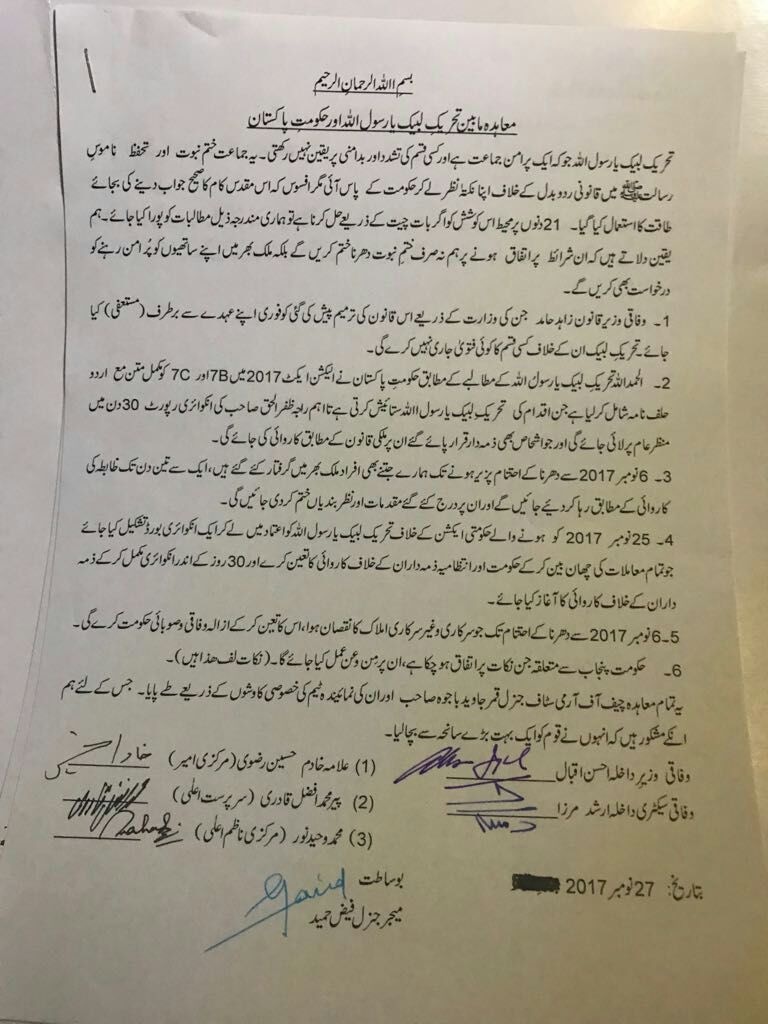

While the then law minister Zahid Hamid resigned, despite reiterating that he wasn’t guilty, the sit-in was finally called off after getting the aforementioned civil-military signatures on the document whose demands included government bringing forth actual culprits of amendments to the Election Reforms Bill, releasing the arrested protesters and removing of all charges against TLP, and action against those responsible for the operation against the group.

The agreement was deemed state surrender, punctuated by the Army’s refusal to step in on behalf of the government. A viral video of Punjab Rangers Director General distributing Rs 1,000 each among the protestors was perhaps the most accurate depiction of the state of affairs.

Numbers game

Given the support at its back, TLP was confident about what lay in the front as this year’s July elections approached. Despite winning 2.2 million votes in the July 25 polls – 2 million in Punjab alone – the TLP couldn’t bag a national assembly seat.

It did, however, form half of the Islamist vote bank, which had risen to around 10% of the overall votes cast – twice as much as 2013 – eventually denting the PML-N’s numbers, and facilitating the Pakistan Tehrik-e-Insaf (PTI) forming the government in the centre and Punjab.

Even so, with nothing to show in terms of electoral strength in the Parliament, the TLP decided to do what it does best: stage nationwide protests against what it dubbed rigging of the elections.

Post-election protests would follow but not for the reasons that the party had envisioned.

Double whammy

The month following the July elections, two back-to-back issues sprung up for the TLP to hop aboard. First was the Dutch lawmaker Geert Wilders’ plan to organise an anti-Islam competition, which he later withdrew. While Pakistan took diplomatic credit for the cancellation of the competition, it was the TLP who had marched from Lahore to Islamabad on the eve the announcement was made that grabbed the biggest chunk of the glory.

The second was the government’s decision to include renowned economist Atif Rehman Mian on the Economic Advisory Council (EAC), which was later withdrawn. The TLP had threatened nationwide protests owing to Atif Mian, an Ahmadi, being given a position in the government’s advisory body. After initially vowing to not bow down to ‘extremist elements’, the government eventually did precisely that.

This would set the ground for more extreme TLP demands and more government backtracking.

Annual ritual

After the Supreme Court overturned Asia Bibi’s death penalty on October 31, establishing that she had been falsely accused the TLP took to the streets all over Pakistan protesting against the acquittal.

In the build up to the verdict the group had already announced that it would retaliate unless Bibi’s death penalty is upheld, meaning that for the second straight November, the group was camped in the capital.

And for the second straight year a state surrender followed with the government promising – at least in the agreement – to put Asia Bibi on the Exit Control List, to allow the review petition against the apex court’s verdict, to not take any action against the protestors and to release those arrested.

And so despite the TLP leadership issuing death threats to the Supreme Court judges, and Army leadership, they managed to successfully challenge the writ of the state without any repercussion.

State surrender

Veteran activist and Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP) Spokesman IA Rehman calls out the weakness of the state as it failed to take any action against the group.

“They were calling out for judges to be killed. They even said anyone who defended Asia Bibi deserve to be killed. Not taking any action against them despite such open threats underscores the weakness of the state,” he said.

Amnesty International’s Deputy Director for South Asia, Omar Waraich urges Pakistan to uphold rule of law in the country in order to deal with elements like the TLP.

https://twitter.com/nayadaurpk_urdu/status/1058408834971119618

“There is a need to safeguard the rule of law, but also to address the flaws and loopholes in the law in the country, which are exploited by [the likes of TLP],” he said.

“There are obvious issues with the blasphemy law for instance. The Amnesty does not believe that anyone should be killed for saying something,” he added.

Modus Operandi

Blasphemy law is one prominent tool that the TLP uses. IA Rehman believes that it facilitates TLP in its modus operandi.

“The group relies on hatred, threats and intimidation – particularly targeting the religious minorities. It is the government’s responsibility to protect the minorities from such threats of violence,” he said.

The most frequently targeted by the group is the Ahmadiyya community owing to their beliefs, which the Constitution of Pakistan has deemed heretical and the TLP deems wajib-ul-qatl.

Amir Mehmood, who is in charge of the Ahmadiyya community’s press office, believes the TLP is a violent manifestation of the anti-Ahmadi sentiments that exist in the society and established by law.

“The constitution calls us kafir and takes away the basic human rights including freedom of religion, freedom of speech, freedom of assembly and others. The sentiments that Khadim Rizvi expresses about the community are those that are prevalent in the society,” he said.

“As long as such sentiments exist in the society, and as long as the law would continue to support them, groups like TLP would continue to flourish.”

Former Foreign Minister Khurshid Kasuri notes that anti-blasphemy activism carries a distinct significance in South Asia.

“Pakistan always takes a prominent stand against anti-Islam cartoons in the West, because they carry special significance in the region. You have the legacy of Ghazi Ilam Din in this region, and similarly since the Ahmadiyya movement originated here as well, so the movement against them is the most prominent here as well,” he said.

“I believe the long-term solution is for Pakistan to approach the OIC and look to establish something universal, which the entire Muslim world agree on.”

Ambitions

Meanwhile, the TLP leadership refuses to be dubbed ‘extremists’ and regularly distances itself from any violence. They maintain that what they’re striving for is simply something that is mandatory for every Pakistani Muslim.

“We want to create the Islamic state that Quaid-e-Azam envisioned,” says TLP spokesman Ijaz Ashrafi. “Which is why Sharia needs to be enforced throughout the country and strict action needs to be taken against anything anti-Islam.”

Ashrafi is adamant that the group has nothing against religious minorities. “We have nothing against Christians, Hindus or members of other religions and try to help them whenever we can. All we ask is that they should live as minorities and get the rights that are sanctioned for them under Islamic law,” he said.

The Ahmadis, Ashrafi says, are a different case. “They pretend to be Muslims when they are not, and hence deserve to be punished for that. There is only one punishment for blasphemy and heresy in Islam, which is what we are striving to ensure.”

On August 1, 2015, 75 Ahl-e-Sunnat leaders pledged allegiance to Khadim Hussain Rizvi as he announced the formation of Tehrik Labbaik Ya Rasool Allah at Karachi’s Nishtar Park.

The Barelvi group’s charter was straightforward: “imposition of Sharia in Pakistan, and the protection of Prophet Muhammad’s (PBUH) honour.

Over three years later, now going by the name of Tehrik-e-Labbaik Pakistan (TLP), Khadim Rizvi’s party has evolved into an entity that can dictate foreign policy, mock the Supreme Court and bring the entire country to a standstill at the drop of a fatwa.

Early days

Tehrik-e-Labbaik’s creation was intended as a pressure group to prevent the government from executing Mumtaz Qadri, who had been sentenced to death for killing former Punjab Governor Salmaan Taseer.

And so it was natural that when the police commando was hanged on February 29, 2016 the Tehrik exploded to the scene with its first protest in the capital.

As an intermittent protest continued in Islamabad during March 2016, the sit-ins were finally called off following seven-point verbal agreement with the government, which carried little significance.

TLP would go on to get the signatures of the civil military leadership on those very points the very next year, owing to an external manufacturing of circumstances that the group made the most of.

The rise

While the Tehrik Labbaik would continue to be a manifestation of the radical brand of Barelvi Islam – making full use of the weaponised blasphemy law – that has become prominent this decade, the year and a half following Mumtaz Qadri’s execution would see the group remain limited to tributes for the man they felt was “judicially martyred” and issuing of scores of fatwas.

It is the latter that gradually brought Khadim Rizvi to the forefront, with his now signature foul-mouthed fatwas targeting anyone he deemed a blasphemer.

These included the state itself, and the current Prime Minister Imran Khan, who in January 2017 was accused by Rizvi of blaspheming and declared a kafir for sharing an anecdote from Islamic history.

Mainstreamed

On August 14, 2017 the Milli Muslim League (MML) an offshoot of Hafiz Saeed’s Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT) and Jamaat-ud-Dawa (JuD) announced its creation in a bid to contest the 2018 general elections.

More imminent, however, was the by-election in the then NA-120 constituency of Lahore, which had been vacated by former Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif after being disqualified by the Supreme Court in the Panama Papers trial in July.

Many believe that Nawaz’s disqualification had the backing of the all-powerful military establishment owing to his trading overtures towards India, and calls for action against Kashmir bound jihadists – spearheaded by Hafiz Saeed – which formed the basis of the Dawn Leaks of October 2016 as well.

Multiple Army officials have revealed that bringing the likes of MML to mainstream was also an Army backed plan, which was not aimed at giving these groups political space, but would eventually dent the then ruling Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz’s (PML-N) vote bank as well.

Among these was the TLP as well.

The rise continues

After capturing thousands of votes in by-elections in Punjab and Khyber Pakhtunkwa, TLP found its moment in the first draft of the Electoral Reforms Bill 2017, wherein the working of the candidate nomination paper had been changed to eliminate its anti-Ahmadiyya clauses.

While the government reinstated those clauses, by then the TLP had established its parallel court demanding the head of those responsible for the changes in the original bill. In November 2017, a two-week choking of the capital through a sit-in at Faizabad Interchange ensued.

While the then law minister Zahid Hamid resigned, despite reiterating that he wasn’t guilty, the sit-in was finally called off after getting the aforementioned civil-military signatures on the document whose demands included government bringing forth actual culprits of amendments to the Election Reforms Bill, releasing the arrested protesters and removing of all charges against TLP, and action against those responsible for the operation against the group.

The agreement was deemed state surrender, punctuated by the Army’s refusal to step in on behalf of the government. A viral video of Punjab Rangers Director General distributing Rs 1,000 each among the protestors was perhaps the most accurate depiction of the state of affairs.

Numbers game

Given the support at its back, TLP was confident about what lay in the front as this year’s July elections approached. Despite winning 2.2 million votes in the July 25 polls – 2 million in Punjab alone – the TLP couldn’t bag a national assembly seat.

It did, however, form half of the Islamist vote bank, which had risen to around 10% of the overall votes cast – twice as much as 2013 – eventually denting the PML-N’s numbers, and facilitating the Pakistan Tehrik-e-Insaf (PTI) forming the government in the centre and Punjab.

Even so, with nothing to show in terms of electoral strength in the Parliament, the TLP decided to do what it does best: stage nationwide protests against what it dubbed rigging of the elections.

Post-election protests would follow but not for the reasons that the party had envisioned.

Double whammy

The month following the July elections, two back-to-back issues sprung up for the TLP to hop aboard. First was the Dutch lawmaker Geert Wilders’ plan to organise an anti-Islam competition, which he later withdrew. While Pakistan took diplomatic credit for the cancellation of the competition, it was the TLP who had marched from Lahore to Islamabad on the eve the announcement was made that grabbed the biggest chunk of the glory.

The second was the government’s decision to include renowned economist Atif Rehman Mian on the Economic Advisory Council (EAC), which was later withdrawn. The TLP had threatened nationwide protests owing to Atif Mian, an Ahmadi, being given a position in the government’s advisory body. After initially vowing to not bow down to ‘extremist elements’, the government eventually did precisely that.

This would set the ground for more extreme TLP demands and more government backtracking.

Annual ritual

After the Supreme Court overturned Asia Bibi’s death penalty on October 31, establishing that she had been falsely accused the TLP took to the streets all over Pakistan protesting against the acquittal.

In the build up to the verdict the group had already announced that it would retaliate unless Bibi’s death penalty is upheld, meaning that for the second straight November, the group was camped in the capital.

And for the second straight year a state surrender followed with the government promising – at least in the agreement – to put Asia Bibi on the Exit Control List, to allow the review petition against the apex court’s verdict, to not take any action against the protestors and to release those arrested.

And so despite the TLP leadership issuing death threats to the Supreme Court judges, and Army leadership, they managed to successfully challenge the writ of the state without any repercussion.

State surrender

Veteran activist and Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP) Spokesman IA Rehman calls out the weakness of the state as it failed to take any action against the group.

“They were calling out for judges to be killed. They even said anyone who defended Asia Bibi deserve to be killed. Not taking any action against them despite such open threats underscores the weakness of the state,” he said.

Amnesty International’s Deputy Director for South Asia, Omar Waraich urges Pakistan to uphold rule of law in the country in order to deal with elements like the TLP.

https://twitter.com/nayadaurpk_urdu/status/1058408834971119618

“There is a need to safeguard the rule of law, but also to address the flaws and loopholes in the law in the country, which are exploited by [the likes of TLP],” he said.

“There are obvious issues with the blasphemy law for instance. The Amnesty does not believe that anyone should be killed for saying something,” he added.

Modus Operandi

Blasphemy law is one prominent tool that the TLP uses. IA Rehman believes that it facilitates TLP in its modus operandi.

“The group relies on hatred, threats and intimidation – particularly targeting the religious minorities. It is the government’s responsibility to protect the minorities from such threats of violence,” he said.

The most frequently targeted by the group is the Ahmadiyya community owing to their beliefs, which the Constitution of Pakistan has deemed heretical and the TLP deems wajib-ul-qatl.

Amir Mehmood, who is in charge of the Ahmadiyya community’s press office, believes the TLP is a violent manifestation of the anti-Ahmadi sentiments that exist in the society and established by law.

“The constitution calls us kafir and takes away the basic human rights including freedom of religion, freedom of speech, freedom of assembly and others. The sentiments that Khadim Rizvi expresses about the community are those that are prevalent in the society,” he said.

“As long as such sentiments exist in the society, and as long as the law would continue to support them, groups like TLP would continue to flourish.”

Former Foreign Minister Khurshid Kasuri notes that anti-blasphemy activism carries a distinct significance in South Asia.

“Pakistan always takes a prominent stand against anti-Islam cartoons in the West, because they carry special significance in the region. You have the legacy of Ghazi Ilam Din in this region, and similarly since the Ahmadiyya movement originated here as well, so the movement against them is the most prominent here as well,” he said.

“I believe the long-term solution is for Pakistan to approach the OIC and look to establish something universal, which the entire Muslim world agree on.”

Ambitions

Meanwhile, the TLP leadership refuses to be dubbed ‘extremists’ and regularly distances itself from any violence. They maintain that what they’re striving for is simply something that is mandatory for every Pakistani Muslim.

“We want to create the Islamic state that Quaid-e-Azam envisioned,” says TLP spokesman Ijaz Ashrafi. “Which is why Sharia needs to be enforced throughout the country and strict action needs to be taken against anything anti-Islam.”

Ashrafi is adamant that the group has nothing against religious minorities. “We have nothing against Christians, Hindus or members of other religions and try to help them whenever we can. All we ask is that they should live as minorities and get the rights that are sanctioned for them under Islamic law,” he said.

The Ahmadis, Ashrafi says, are a different case. “They pretend to be Muslims when they are not, and hence deserve to be punished for that. There is only one punishment for blasphemy and heresy in Islam, which is what we are striving to ensure.”