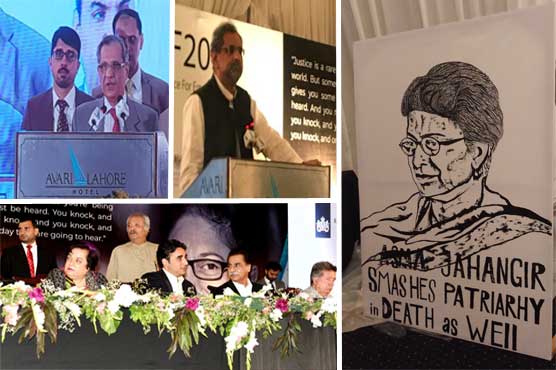

The Asma Jehangir Memorial International Conference on human rights this weekend in Lahore has to have been a good thing. It is implied in the title, human rights and Asma Jehangir, recently deceased, undeniably influential, and to all intents and purposes one of the key figures to emerge against military and Islamist rule in Pakistan over the past 30 odd years. This conference was perhaps the biggest in a string of references and tributes organized by Asma’s friends and well-wishers since her sudden demise from a heart attack 6 months ago.

This morning on social media there were messages from those invited to speak, reiterating Asma’s achievements, and some from old students talking about how much they learned. Yesterday’s papers covered the Chief Justice of Pakistan, Mian Saqib Nisar, and his speech at the conference; at 1:30 pm, a press conference at the Lahore Press Club announced that a reference had been filed against the Chief Justice for judicial misconduct by the Women’s Action Forum. On Saturday the newest Islamo-fascist group in the country Tehreek Labbaik ya Rasoola Allah with its 2million-strong vote bank threatened the state with violence and promised the wholesale massacre of the judiciary should Aasia Bibi, a poor Christian woman accused of blasphemy, be acquitted and freed from the jail she has been languishing in without trial for the past 8 years.

The conference schedule devoted the first morning to ‘Remembering Asma’ followed over two days by sessions on democracy, the independence of the judiciary, gender equality, the rise of religious extremism, the role of civil society, UN global goals on sustainable development and so on, punctuated by tributes to Asma.

At the surface there is very little to object to here, it meets expectations and follows an established pattern of such conferences everywhere; it touches on all the key themes we would expect in a liberal forum in a darkening world. This was, however, not what we needed here, now, with the polity spitting at the seams, and the human rights world, its prominent members, those with a history of activism in the 80s, the NGOs that these early activisms spawned, the international donors, and the others invited to speak who cannot possibly be categorized as bastions of human rights, the political elite, former prime ministers and future ones perhaps, ministers, advocates, lawyers, judges, should have known better - our current crisis is made from events such as these and what they signify; they are symptomatic and feed the very problem they aim to address.

Somewhere down the line, and exacerbated by global shifts and market demands, human rights has become a product for those who can afford to consume. The stakes are high and the market place has its demands, its requirement for particular ingredients, and for identified consumers whose tastes and proclivities have to be catered to, and whose ideological, social and psychological comfort has to be protected and supported. The consumers of the human rights equation are in Pakistan primarily members of the Pakistani liberal elite, anachronisms in their own right and responsible as a class for the abrasion of the very rights they endorse. The elite capture by which possession by the elite is extended and by which zones of exclusion are demarcated is by definition also the source of discontent and the site of perpetuating alienation which has led the majority population of the country to reject the liberal ideas espoused by the liberal elite for the more egalitarian space of Islamic conservatism and religious fundamentalism; even the army and authoritarian rule offer equalities that the liberal elite consistently deny.

This Asma Jehangir conference was perhaps a manifest reminder of antagonisms at the heart of the human rights question, and of the reasons why fundamental rights as defined through and emergent from a liberal humanist tradition fail to take root in this country that is our home.

The conference was advertised ahead of time in a number of English language dailies and was held this weekend at the Avari Hotel in Lahore, a 5-star venue where concepts and genealogies of ‘natural’ difference are proposed in the quotidian and deeply embedded in the purpose and meaning of space and place. Avari’s entrance hall sports a sweeping glass staircase, a shimmering and precipitous blue erupting from the side of a wide expanse of chandeliered lounge; the walls to the compound are high, and heavily guarded. On any given day the only poor or lower middle classes permitted inside are those who clean the floors, open doors, chauffeur cars, guard the gates, they are uniformed, invisible and smiling. No one just enters off the street, the street is categorically there only to serve. Exclusion and exclusivity, despite the conference theme, were already established subtexts at the onset through language and location and the access denied by both.

The bulk of the speakers and indeed the audience, by design it seems, were from the upper middle and upper class ‘left’, the neoliberal right, and from the no-man’s land in between and on either side where people follow celebrity and fashion rather than any staked claim to a political ground. There were representatives from international agencies, and ambassadors though none from the global south, and university students newly born, seeking a place of possible history, potential belonging and definitive knowledge, and there were some like IA Rehman whose origins are elsewhere but who have been absorbed over the years by their clarity and work into a nexus of power that lets few in.

There was I believe a smattering of trade union leaders and others invited, those who Asma and the NGOs may have worked with over the long term, others to whom aid may have been at some time dispensed indirectly, but the fact is that the primary stakeholders in the struggle for human rights in Pakistan, those who are at the receiving end of this country’s failure to deliver, those whose lives are diminished and made precarious by systems of governance and social divides were not there, not represented to any real degree, and excluded even while present by the dominance of English as the conference language.

Though I believe that the invitations to the poor were not perhaps premised on other self-interests (genuine relationships do develop over long term contact and in the unlikeliest of places), cynically speaking the nominal presence of the poor, the disenfranchised and the marginalized is also a required ingredient in events such as these; it is proof of authenticity, and an enactment of inclusion that anchors the rest to seemingly solid ground. There is much value, we know, in a care worn face.

I do not know how many of those dispossessed by Pakistan’s globalized elite, if any, were permitted to take the stage and address the political and economic class that is responsible for stripping them of their rightful ownership. I do not know if truth to power can be spoken in any meaningful way, if it is power that speaks to power. I do not know whether the conference was organized to project, promote and network, or whether there was an honest and real desire to address the visceral, painful, bodily space within which most live here, and die.

I do know that most oft heard names in the human rights world were there. I know that there was no protest, no relinquishing of the stage, no boycott inspired by the fact that Asma Jehangir’s organization (AGHS, now taken over, I believe by her daughter Sulema) had seen fit to invite the Chief Justice of Pakistan to speak, one of the main architects of authoritarianism in Pakistan today, a man whose contempt for the constitution is visible, whose actions today diminish the possibility of a future premised on fundamental rights, democratic principles and the devolution of power to the people. Some I believe (members of the Women’s Action Forum) did not attend the session by the Chief Justice, but attended the rest with aplomb. I also know that these members of WAF, who were young women with young children at the time and had everything to lose, spent the 80s fighting the country’s most brutal dictatorship on the streets of Lahore. I remember their clarity, their courage, and their refusal to compromise. I know that they know deep down that this weak exit from the Chief Justice’s session was not a protest, but at most a palliative, an occupancy of all spaces and positions simultaneously and none at all. And I wonder what fell by the wayside.

For all those there who know better, I ask what happened, I ask why the Chief Justice was invited and why there was no response at the conference from the same people who spent the weekend railing against authoritarianism and its impacts?

Words are powerful, but not so when they are weakened by visible contradictions and seeming hypocrisies. What I was hoping from this conference that appears to have been waylaid by another world though still full of familiar faces, was a critical and reflective take on what went wrong. Today this country and its people are aligned with authoritarianism, with an increasingly brutal religiosity, and with neoliberal paradigms fed from on high with promises of deliverance. I was hoping for an honest reflection about why the narratives of the progressives have failed to capture public imagination, and why there is despite all, so much mistrust here on the ground of those who claim the fight for fundamental rights on behalf of those who have none. I would have liked something that examined the role of the NGOs, their structural failings, and the effects of the NGOization of activism and the corporatization of the NGOs on stated purpose. I was looking perhaps for less celebration, because the poor being represented in their absence have very little to celebrate.

I was hoping that Asma Jehangir’s legacy would be honoured through a critical and thoughtful lens, an acknowledgement of her failings and weaknesses along with the rest, so that a better way forward could be found. I was hoping for an open forum, with a real invitation to those most impacted by the absence of rights in Pakistan, in a space that welcomes all to come and listen and be heard. I was hoping for a conversation.

Ideological seduction proposes that we can become the embodiment of a moral high ground. It is a fiction, a process that needs its histories, its cultural locations, its theoretical underpinnings, its narratives, its significations, its heroes, its icons and its ghosts to aid the process of becoming. Asma posthumously for the progressives, and Mumtaz Qadri for the far right are needs must ghosts whose 2-dimensionalization and deification serves a purpose. The difference is that though these reductions pose no immediate threat to the Shariah weaving wave of new claimants to the country’s political thrones, for the progressives such reductionism is the site of a perilous contradiction which may ultimately completely remove the ground on which they stand.

The message that has been delivered, unwittingly perhaps, is that those that were present are all in it together connected not by ideals but by a locus of power and privilege that is relentless in what it takes from the people, and which is supported in a common end by those from the West who give with one hand and take more with the other. A conference premised on context failed to recognize the context in which it occurred, by its very nature, by where it was held, and by whom it chose to invite and exclude. Regardless of resolutions or well-meaning intent its very insularity may have undermined its purpose, and driven us further towards places from which there is no return.

Privilege blinds and voices carry.