On August 18, 2018, the chairman of PTI, Imran Khan, became Pakistan's 22nd prime minister. His party had won the most seats during the July 25 general election. With a handful of allied parties, PTI managed to form a simple majority government at the centre.

PTI, which was formed by the charismatic former Pakistan cricket captain and celebrity, Imran Khan, in 1995, had failed to gain any mentionable momentum till its sudden rise in 2011.

The party was born as a reaction against the country’s two main mainstream parties, the PPP and the PML-N. Khan believed that both these parties were entirely corrupt and detrimental to the country’s internal and external interests in the post-Cold-War international order.

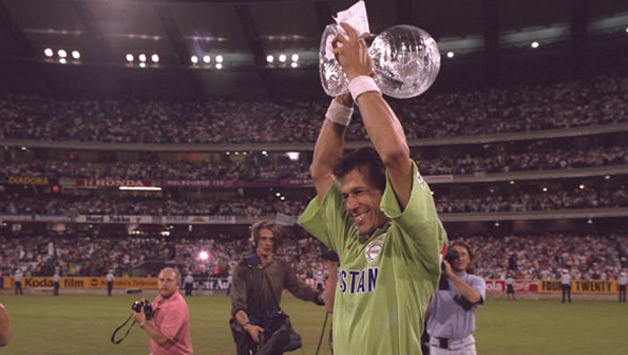

At the time of forming his party, Khan was going through a spiritual transformation of sorts. Having lived a completely secular life as a celebrity sportsman and ‘playboy’, Khan went through a process of becoming a ‘born-again Muslim’ after retiring from cricket in 1992. He retired on a high note after leading the Pakistan cricket team to its first ever World Cup victory.

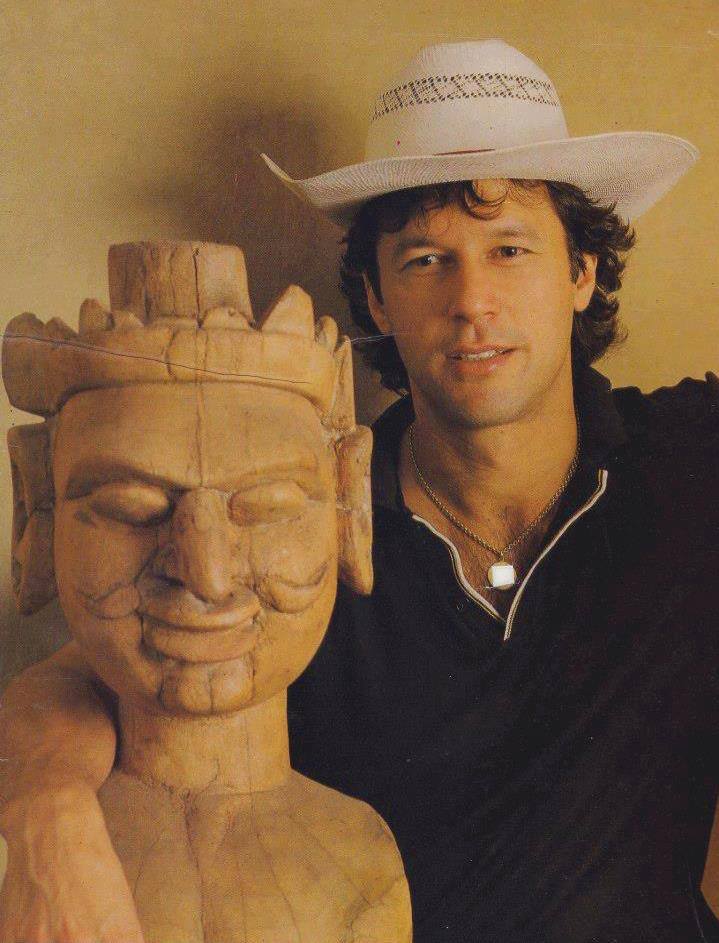

Imran in 1984.

Winning the 1992 Cricket World Cup.

With third wife, Bushra.

Brand IK

Even though till 2011, his party was hardly ever taken seriously by the electorate, Khan robustly continued to build himself into a political brand which eventually got the attention of the country’s urban middle-classes.

Through regular appearances on TV talk shows, Khan constantly unleashed his angry tirades against corruption and the country’s reliance on US aid. He was also against Pakistan’s involvement in the ‘War on Terror’. He bemoaned that Pakistan was fighting America’s war against a people who could be pacified through peaceful means.

As the distance between the two mainstream parties, the PPP and PML-N, and the military continued to expand, the latter began to eye Khan as a possible future prime minister who could be easier to work with compared to the two older parties that were by then openly suspicious of the military’s political interests.

Khan has been vehemently criticised for holding reactionary views by his opponents. One wondered, if true, then exactly how could his benefactors in the military see him reconcile his views to the more moderate ones indoctrinated within the military by Gen Raheel.

According to some observers, PTI’s sudden expansion in 2011 was a combination of two factors: the growing urban middle-classes and their frustration of not being able to transform their economic power into political influence; and the military high command’s desire to patronize PTI and bring the party’s political narrative in line with that of the military’s.

At the time the military’s narrative didn’t necessarily mean the one which it eventually adopted under General Raheel from 2013 onward. But one can claim that what began to emerge during the Raheel tenure had already begun to evolve after 2010, mainly due to the way the extremists were so conveniently bullying state writ in various regions of the country.

PTI witnessed increasing support from the country’s urban middle-classes from 2011 onward.

Imran had taken populist stands against military action against the TTP, insisting that Pakistan was being made to fight someone else’s war. Nevertheless, this narrative received a body blow when the extremists slaughtered over 140 students in December 2014 and General Raheel forced the parliament to green light an all-out military operation against the TTP. Eventually, Imran and his PTI too became signatories of the resolution passed by all parties to back the operation.

Imran was gradually nudged to adopt a more moderate stand in this context by his well-wishers in the armed-forces. Parties such as the PPP, MQM and ANP had already adopted such a stand but the coalition government that they were a part of between 2008 and 2013 was just too weak and shaky to popularise its anti-extremist outlook.

They got no support whatsoever in this respect from PML-N and PTI and nor was the military at the time willing to undertake the kind of action which Gen Raheel finally initiated.

PML-N too, eventually, swung towards holding a centrist position a year after it won the 2013 election. But for various political reasons, the party was reluctant to implement the equally important National Action Plan (NAP) that was drafted to tackle the non-militant aspects of extremism.

The PML-N government further strained its relations with the military by trying to hasten amicable economic and political relations with India during a period when India had swept an anti-Pakistan Hindu nationalist to power.

Civil-military relations continued to deteriorate during the PML-N regime (2013-2018).

The 2018 elections were controversial. Most parties, except the PTI, claimed that they were rigged with the help of the military. Fact is, over the years, PTI had built enough traction for itself as a populist party headed by a charismatic leader who had never been accused of being corrupt.

Observers now believe that PTI, which won 117 seats out of a total of 272 National Assembly seats, was poised to win between 90 to 95 seats. These observers claim that what made the election controversial was not PTI’s (albeit slim) victory; but the fact that it was ‘gifted’ an extra 10 to 15 seats through last-minute tampering engineered by the officials of the Election Commission of Pakistan supposedly ‘on the insistence of certain influential men in state institutions’.

Khan has been vehemently criticised for holding reactionary views by his opponents. One wondered, if true, then exactly how could his benefactors in the military see him reconcile his views to the more moderate ones indoctrinated within the military by Gen Raheel.

Pakistan’s off and on relationship with Muslim Modernism

The military under Gen Raheel and then General Bajwa has been looking to blunt the extremist narrative by adopting various aspects of what became to be known as ‘Muslim Modernism’ in the late 19th century.

After the complete fall of the Muslim empire in India in the 19th century, most Muslim thinkers had responded to the fall by rebuffing the crumbling reminiscences of their imperial past.

They began to espouse certain notions of nationalism to find their place in the shifting standards of a new global order.

One main outlet of early Muslim nationalism in South Asia encouraged the embrace of modern education and the sciences so that an educated and informed Muslim nation could emerge in India to face the challenges of British colonialism.

This pursuit was academically driven by an emerging Muslim middle-class intelligentsia in South Asia. It saw the Muslims of India as a distinct cultural entity, united by an urge to refresh its shared religion through a more rational reading of the Muslim sacred texts.

Some of the leading scholars who contributed to this modernist Muslim project were Sir Syed Ahmad Khan, Syed Amir Ali, Chiragh Ali, Muhammad Iqbal, Ghulam Ahmad Pervez, Khalifa Hakim and Dr. Fazal-ur-Rahman Malik.

Pakistan’s founder, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, turned this largely intellectual tendency into a powerful political movement for a separate Muslim state which was to be formed to fully express and implement the modernist Muslim project.

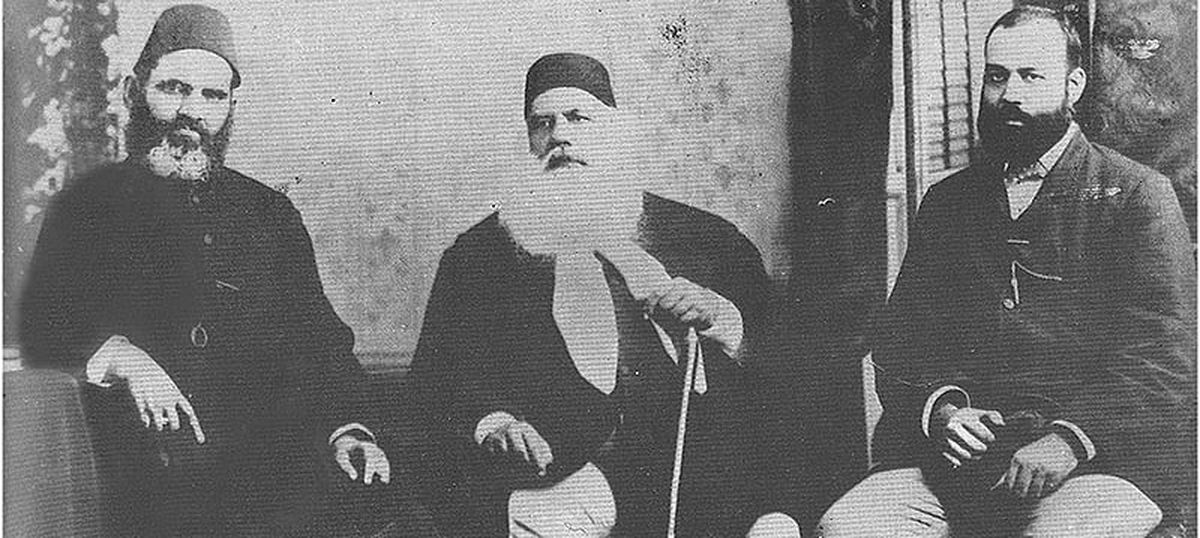

19th century Indian Muslim scholar, Syed Ahmad Khan (centre) was one of the main architects of ‘Muslim Modernism’ in South Asia.

Pakistani nationalism, which emerged from this strand of Muslim nationalism, was thus inherently pluralistic. Till the mid-1970s, the government and state institutions of Pakistan continued to explain Pakistani nationalism as a modernistic and progressive expression of Islam.

But some dire happenings, such as the East Pakistan debacle in 1971, split the Pakistani polity. One overriding segment of this polarization began to be expressed through certain convoluted reactionary ideological alternatives.

These alternatives succeeded in prompting a popular response from a new generation of middle and lower-middle-class Pakistanis impacted by the 1971 debacle. This post-1971 existentialist-nationalist narrative was also backed by certain oil-rich Arab regimes that had seen modernist Muslim ideas such as Muslim Modernism, Islamic Socialism, Ba’ath Socialism and Arab Nationalism as hazards to their ideas of faith and politics.

As a response to the mounting acceptance of this alternative version of Pakistani nationalism, the Pakistani state began to readjust the country’s ideological status quo by co-opting various features of the new narrative; even to the extent of forgoing many of the state’s original ideas of Pakistani nationalism.

The gaps created by the gradual erosion of the original ‘modernist’ nationalist narrative began being filled by ideas, which, ironically, had earlier been shelved by the Pakistani nationalist intelligentsia.

The emerging alternative was opposed to the modernist Muslim nationalist narrative. It censured it for going against ‘Islamic universalism’. But many decades later, especially from the mid-1970s onwards, when such ideas managed to root themselves in the state and polity of Pakistan, the country was thrown into an existentialist catastrophe.

For instance, many young Pakistanis today seem to be detached from the original ideas of Pakistani nationalism because as students they were bombarded with ideas of a rather myopic and isolationist version of Pakistani nationalism. A version which was never part of the idea of Pakistani nationalism weaved by the country’s founders.

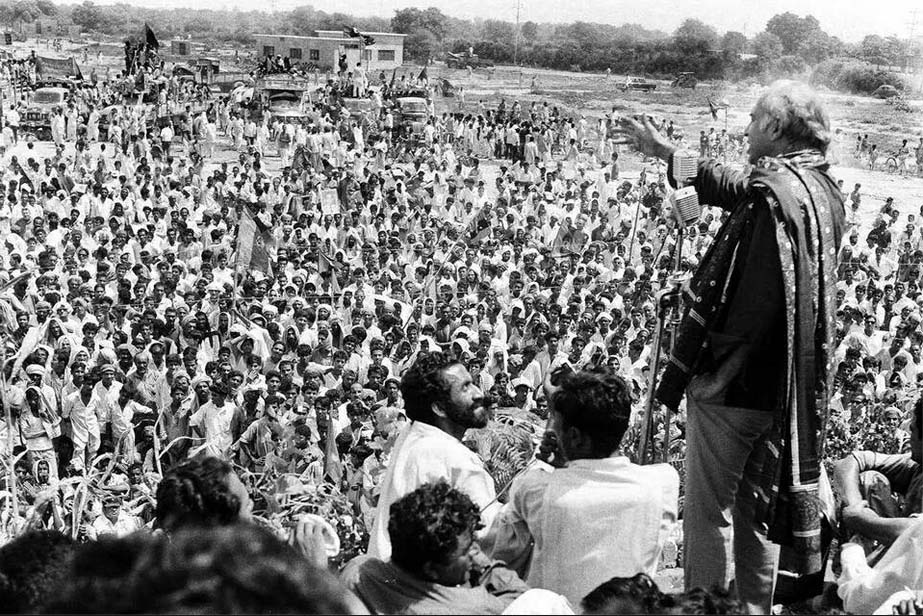

Jinnah converted the intellectual modernist Muslim project into a populist political pursuit which eventually gave birth to Pakistan.

The Ayub Khan regime (1958-69) institutionalised Muslim Modernism as central plank of Pakistani nationalism.

The ZA Bhutto regime (1971-77) turned Muslim Modernism into a populist and left-leaning expression. But the government then began to quickly rollback its idea of Muslim Modernism from the mid-1970s onwards as the polity began to shift to the right.

The Zia dictatorship (1977-88) managed to completely erode the Muslim Modernism project and replaced it with a more belligerent and myopic strand of Pakistani nationalism.

Which way would Khan go?

To counter the proliferation of extremist ideas within the polity and also in state institutions, Gen Raheel initiated a gradual re-think in the way the military had begun to understand itself -- especially ever since the reactionary Gen Zia dictatorship in the 1980s.

Gen Raheel had to do this because this time the military was to fight an enemy that was using almost the same religious rhetoric and slogans introduced in the military by Zia. So it became vital for Gen Raheel to set and communicate a differentiation between the Islam being followed by the soldiers and one being propagated by the militant outfits.

This is why Gen Raheel was also heavily invested in making the government activate NAP, whose many aspects reflect certain doctrines of Muslim Modernism.

Gen Raheel was heavily invested in activating NAP many of whose aspects are contemporary versions of classic Muslim Modernism.

So if one is to believe the allegation that the military was aggressively creating the scenario for a PTI victory, one can also assume that Khan is being nudged to uphold the changing narrative within the armed forces now reinforced by certain modernist aspects?

Khan’s first address to the nation cleared the air a bit. These ‘modernist’ aspects came forth in Khan’s speech as well, when, just as most Muslim modernists - from Syed Ahmad Khan, to Iqbal, Ayub, Bhutto to Musharraf - had done before him, Khan too insisted that Islam was a living religion which was entirely modern and that its inherent democratic, pluralistic and compassionate disposition had inspired western democracy and the Scandinavian concept of the welfare state.

This was classic Muslim Modernism -- navigating a path between secularism and Islamic conservatism and/or adopting modernist western ideas by finding their roots within Islam’s sacred texts and ancient history.

Just how Khan (and more so, the military) plans to tread this path to neutralise the lingering impact of the post-1970s myopic nationalist narrative remains to be seen -- even though the PTI regime’s decision to oust an Ahmadi advisor due to pressures exerted by the religious parties and elements from within Khan’s own party, rudely contradicted his own vision of delivering a ‘compassionate regime that believed in meritocracy.’

But there is no doubt, the answers still need to be explored from within the forgotten cannons of Muslim Modernism.