Now that our Independence from British colonizers is 71 years old, and we are rapidly losing people of partition generation – memoires, archives, oral records and images are becoming more and more important for us. Following the long years of silence, partition has emerged as a significant field in academia and a celebrated genre in all fields of arts and fiction.

The cartographic line that stamped the creation of Pakistan by dividing the Indian subcontinent into Hindu-India and Muslim-Pakistan not only reconfigured the map of South Asia but also altered the lives of millions of people who inhabited this land. Partition, while on one hand celebrated the historic event of decolonization of India from British colonial rule, on the other hand marked one of the worst events of human suffering due to the largest movement of peoples in human history. Although migration was not made compulsory, however, it was neither a matter of choice for the people who were thrown into this exodus.

In Pakistan, we have heard stories of monstrosities of Hindus and Sikhs on helpless Muslims, while people on the other side of the border have similar accounts of partition loaded with the atrocities brought by Muslims on migrating Hindus and Sikhs. Hence, it is not very difficult to understand that partition followed by migration was actually an event of abomination for all humankind.

Above and beyond the religious, ethnic and national identifications, they were humans who suffered that unbearable violence, unrecoverable trauma and irreparable loss. In addition to the bodies that were butchered, there were souls that were torn and ripped in those bodies and were altered forever. Sadly, the political hatred that caused this havoc has continued to haunt us even today after so many years, illusively painting this intricate montage in national colors – Green and Saffron – underlying which is its monochromatic nature that signifies humanity.

Nonetheless, there are ways in which we can take a retrospective view and revise our perceptions by revisiting the past through the frozen memories. There is a sheer absence of visual records of partition and migration but photographs of American photojournalist Margaret Bourke-White are a direct gateway to come into contact with that event through a first-hand account. Here, I will analyze a few pictures from her collection, a collection I call frozen tears. These pictures invite us to reconsider our lens through which we usually look at partition and the ruination it has caused to the humans who lived and suffered through this bloody affair.

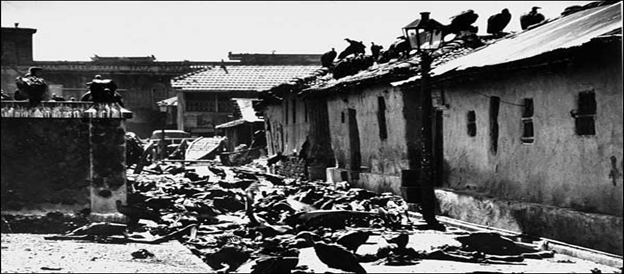

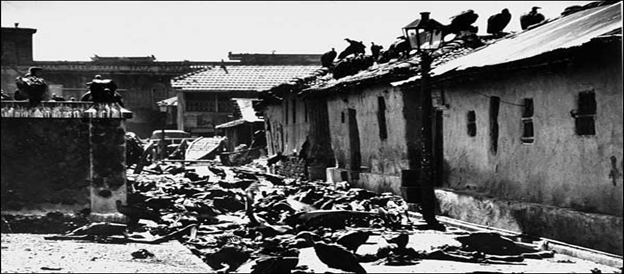

The street in this picture is a ruin per se. There are no individual identities anymore as these bodies are reduced to a dead mass just as they were reduced into colonial subjects by their British colonizers, when they were alive. Broken windows, torn sheds and damaged walls cannot speak about the identity of people who turned this street full of life into a dead ruin. The only living creatures that can be spotted in this picture are vultures that symbolize predators who are going to enjoy this human feast prepared by humans. Silent echoes of these ruins definitely shout for the brutality of their human perpetrators and the pain those assailants have induced. However, it cannot inform us about what these bodies desired when they were alive. They endorsed partition or not? They supported Jinnah or Gandhi? They wanted to be in Pakistan or in India? Why were they killed and who killed them? All these questions remain unanswered as they are no more alive to answer them. They have now become a part of a national misery.

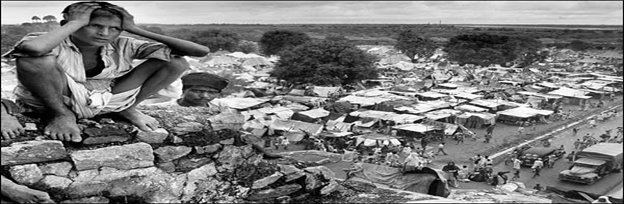

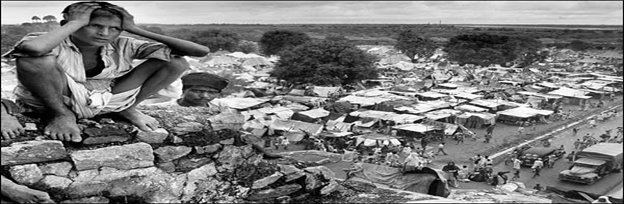

This picture not only reflects confusion but it is a confusion in itself. No one can tell if the boy in the picture is a Hindu or a Muslim. His expressions reflect his worries – hard to say if his worries are for the unforeseen future or the seen past? The boy represents the sentiments of the people who are hoarded like cattle in this refugee camp – dehumanized, uprooted, unsettled and uninstalled. They are in state of confusion, shock and distress. Are they here willingly because they believed in the idea of partition or they are here because they happen to exist on this particular land on this particular point in time? They are here because they are Muslims or Hindus or they are here because they are mortal humans who are vulnerable to death that can be induced and forced upon them? They are migrating because they think they belong somewhere else or they are forced to migrate because it was impossible for them to stay and stay alive in the places where they lived for years?

These women are not labeled with any identification marks but they symbolize those unprotected assets that were left behind by the immigrants and available for looting as their protectors were gone. They are more susceptible than other humans not because of their religious or national affiliation but because they are born with valuable genitalia; breasts and vaginas. Their physical assets make them more plunderable than killable, reducing them to the sites of pleasure and punishment.

It is high time to realize that partition should not only be studied as a nation building project under the echoes of antagonistic political jingoism. These photographs and many other sources like these are important reminders to reconsider the dominant narratives. We should continuously challenge the preconceived notions by pushing forward some alternative ideas that suggest a more humanistic and holistic approach, only then we will be able to make peace with this continued dilemma that makes partition an unfinished project and a lived reality even today.

The cartographic line that stamped the creation of Pakistan by dividing the Indian subcontinent into Hindu-India and Muslim-Pakistan not only reconfigured the map of South Asia but also altered the lives of millions of people who inhabited this land. Partition, while on one hand celebrated the historic event of decolonization of India from British colonial rule, on the other hand marked one of the worst events of human suffering due to the largest movement of peoples in human history. Although migration was not made compulsory, however, it was neither a matter of choice for the people who were thrown into this exodus.

In Pakistan, we have heard stories of monstrosities of Hindus and Sikhs on helpless Muslims, while people on the other side of the border have similar accounts of partition loaded with the atrocities brought by Muslims on migrating Hindus and Sikhs. Hence, it is not very difficult to understand that partition followed by migration was actually an event of abomination for all humankind.

Above and beyond the religious, ethnic and national identifications, they were humans who suffered that unbearable violence, unrecoverable trauma and irreparable loss. In addition to the bodies that were butchered, there were souls that were torn and ripped in those bodies and were altered forever. Sadly, the political hatred that caused this havoc has continued to haunt us even today after so many years, illusively painting this intricate montage in national colors – Green and Saffron – underlying which is its monochromatic nature that signifies humanity.

Nonetheless, there are ways in which we can take a retrospective view and revise our perceptions by revisiting the past through the frozen memories. There is a sheer absence of visual records of partition and migration but photographs of American photojournalist Margaret Bourke-White are a direct gateway to come into contact with that event through a first-hand account. Here, I will analyze a few pictures from her collection, a collection I call frozen tears. These pictures invite us to reconsider our lens through which we usually look at partition and the ruination it has caused to the humans who lived and suffered through this bloody affair.

"The street was short and narrow. Lying like the garbage across the street and in its open gutters were bodies of the dead."

The street in this picture is a ruin per se. There are no individual identities anymore as these bodies are reduced to a dead mass just as they were reduced into colonial subjects by their British colonizers, when they were alive. Broken windows, torn sheds and damaged walls cannot speak about the identity of people who turned this street full of life into a dead ruin. The only living creatures that can be spotted in this picture are vultures that symbolize predators who are going to enjoy this human feast prepared by humans. Silent echoes of these ruins definitely shout for the brutality of their human perpetrators and the pain those assailants have induced. However, it cannot inform us about what these bodies desired when they were alive. They endorsed partition or not? They supported Jinnah or Gandhi? They wanted to be in Pakistan or in India? Why were they killed and who killed them? All these questions remain unanswered as they are no more alive to answer them. They have now become a part of a national misery.

“With the tragic legacy of an uncertain future, a young refugee sits on the walls of Purana Qila, transformed into a vast refugee camp in Delhi”

This picture not only reflects confusion but it is a confusion in itself. No one can tell if the boy in the picture is a Hindu or a Muslim. His expressions reflect his worries – hard to say if his worries are for the unforeseen future or the seen past? The boy represents the sentiments of the people who are hoarded like cattle in this refugee camp – dehumanized, uprooted, unsettled and uninstalled. They are in state of confusion, shock and distress. Are they here willingly because they believed in the idea of partition or they are here because they happen to exist on this particular land on this particular point in time? They are here because they are Muslims or Hindus or they are here because they are mortal humans who are vulnerable to death that can be induced and forced upon them? They are migrating because they think they belong somewhere else or they are forced to migrate because it was impossible for them to stay and stay alive in the places where they lived for years?

“Families were cut to half as men were killed leaving women to fend for themselves.”

These women are not labeled with any identification marks but they symbolize those unprotected assets that were left behind by the immigrants and available for looting as their protectors were gone. They are more susceptible than other humans not because of their religious or national affiliation but because they are born with valuable genitalia; breasts and vaginas. Their physical assets make them more plunderable than killable, reducing them to the sites of pleasure and punishment.

It is high time to realize that partition should not only be studied as a nation building project under the echoes of antagonistic political jingoism. These photographs and many other sources like these are important reminders to reconsider the dominant narratives. We should continuously challenge the preconceived notions by pushing forward some alternative ideas that suggest a more humanistic and holistic approach, only then we will be able to make peace with this continued dilemma that makes partition an unfinished project and a lived reality even today.